Nashville’s black community has always been resilient in the face of adversity. While, most city’s education systems for blacks was contingent on the sacrifices of missionaries traveling south to start schools for slaves and free blacks. Nashville’s educational system possessed a unique story often left out of textbooks today. Sadly, the narrative is often ignoring the brave efforts by southern literate blacks, whether free or enslaved, who built their own scholastic institutions instilling pride and tradition of a strong education and Nashville’s distinction of 30 years of independently owned and operated black schools.

Nashville’s black community has always been resilient in the face of adversity. While, most city’s education systems for blacks was contingent on the sacrifices of missionaries traveling south to start schools for slaves and free blacks. Nashville’s educational system possessed a unique story often left out of textbooks today. Sadly, the narrative is often ignoring the brave efforts by southern literate blacks, whether free or enslaved, who built their own scholastic institutions instilling pride and tradition of a strong education and Nashville’s distinction of 30 years of independently owned and operated black schools.

It was Monday, March 4, 1833, the middle of the Great Revivals. Tennessee’s own, Andrew Jackson, 7th president of the United States, was being sworn in for his second term in the White House. Meanwhile, Alphonso M. Sumner, a free black barber, was embarking on his own historic journey. Alphonso Sumner, opened a clandestine school for Nashville’s black children. Cloaked in secrecy from most of his elite white customers on the heels of Nat Turner’s recent uprising, Sumner used his spare time from the barber shop to teach blacks how to read and write.

Courageously, the school’s enrollment grew from 20 students to approximately 200 by 1836, which was no small feat after cholera and smallpox outbreaks lead to forced closures for moths periodically throughout the years. In the beginning, Sumner banked on the sympathy of white Nashvillians, however, he fell out of favor with Nashville’s white elite and they began invoking terror on local blacks.

In an effort to discredit Alphonso Sumner, he was accused of writing and sending two letters to runaway slaves from Nashville who escaped north through the Underground Railroad. This act implied that Sumner had helped them escape and knew their location. To instill fear into all Sumner’s pupils, he was nearly whipped to death by white vigilantes and forced into exile in Cincinnati in 1836. He became an abolitionist and publisher of the Disfranchised America, Cincinnati’s first black newspaper.

Sumner’s school remained closed until 1838. In 1837, Nashville’s Mayor, Henry Hollingsworth, unsuccessfully gained public support for a school for free black children. Black families remained determined to receive an education, resulting in Wadkins’ takeover of the school.

A petition by a free blacks fortified authorization to open a school for free black children, on the condition they were taught by a white man. Soon after, a free black man hired John Yandle, a Wilson County white teacher. Yandle solicited the help of Daniel Wadkins, a black preacher in the Disciples of Christ denomination and one of Sumners’ teachers, as well as, Sarah Porter Player, another free black.

Yandle resigned under threats of white vigilantes and violence. Player opened a school in her home in 1841. Wadkins also opened his own school in 1842 maintaining the educational efforts of black Nashvillians over the course of the next decade. His school remained in operation despite being forced to move it 6 times during the next 14 years.

By 1850, nearly 83% of free Negro children and half of free black adults could read and write in Nashville. Many of whom had been educated by Sumner and Wadkins.

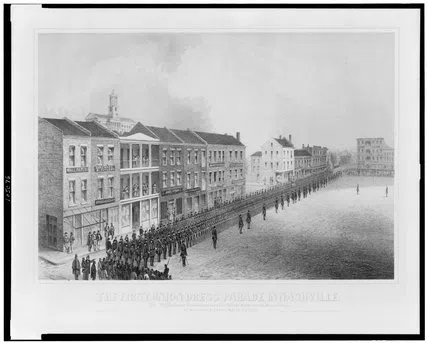

Based on the fear that blacks across the south would become educated and spark an up rise like Nat Turner, Nashville’s City Council instituted a series of severe restrictions on black life. Wadkins and Player were forced to close their schools in 1856 and an ordinance was issued that included a $50 fine for whites found teaching blacks. This ended the formal black education system in Nashville until the Civil War.

Despite ordinances like, “there shall be no assemblage of Negroes after sundown for the purpose of preaching; and no colored man shall be allowed to preach colored people and no white man after night” being issued, Nashville is now uniquely home to four historically black colleges and universities — Tennessee State University, Fisk University, Meharry Medical College and American Baptist College and boasts the former Roger Williams University and Tennessee Central College. These institutions of higher learning are a testament to the triumphs of Nashville’s once dark history of schoolhouses torched by vigilantes to a trailblazer in African American graduates and cream of the crop in American history.